We’ve been looking at exotic spices—spices that named the Spice Islands. Spices that stretched the world map from letter size to double gatefold pullout! Well, it’s time for a down-home, truly accessible spice—mustard. The universally loved seeds grow all over the world. Worldwide, people consume more than 700 million pounds of mustard each year, making it one of the world’s most popular and widely used spices.

Mustard is a member of the Brassica plant family, making it a relative of cabbage, broccoli, turnips, and radishes. The plant bears tiny, round edible seeds as well as tasty leaves.

Koehler’s Medicinal Plants 1887, Copyright expired.

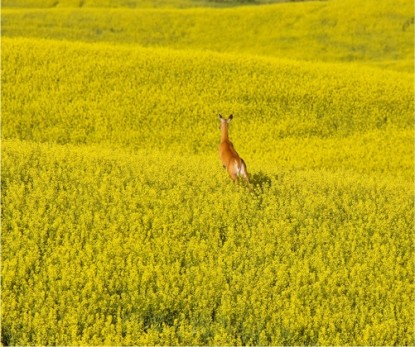

Mustard grows as an annual, cool season crop, native to temperate regions of Europe, the Mediterranean, and Asia. Ancient farmers grew mustard as an herb in Asia, North Africa, and Europe making it one of the earliest domesticated crops. Mustard is raised as a specialty crop in North Dakota, Minnesota, Montana, as well as in the prairie provinces of Canada. In fact, Canada’s farmers satisfy about 85% of the world’s demand for mustard seed. In addition, Canada is the world’s second-largest mustard producer as well.

A deer crosses one of the great expanses of mustard crops in Saskatchewan, Canada’s leading mustard producing province.

Written accounts of mustard reach back 5000 years. Early uses of mustard were primarily medicinal. Pythagoras employed mustard as a remedy for scorpion stings. Hippocrates relied on mustard for a variety of medicines and poultices including mustard plasters applied to “cure” toothaches.

Mustard as a condiment dates back to the early Romans. A recipe for mustard appears in Apicius, the 4th century Roman recipe collection. The recipe begins with ground mustard seed and calls for the addition of thirteen other ingredients. The mixture produced a glaze for spit-roasted boar, or wild pig.

Most likely, Romans brought mustard to what is now France. “Dijon mustard” originated in the 1850s, when a Dijon mustard maker used the acidic “green” juice of not-quite-ripe grapes in place of vinegar. Near the end of the 18th century, Auguste Poupon agreed to fund production of Maurice Grey’s own recipe for Dijon mustard which was white wine based.

Have you any Grey-Poupon?

English mustard makers combined coarse ground mustard seed with flour and cinnamon. They moistened the mixture, and formed it into balls to be dried. The mustard balls stored well and could be combined with vinegar or wine to make mustard paste as needed. In the 1860s, Jeremiah Colman perfected a technique that greatly changed mustard making. He succeeded in grinding mustard seeds into a flour-like powder without generating (thermal) heat. Any heat generated during grinding brings out the mustard’s oil. Once the oil is exposed, it evaporates and takes mustard’s characteristic flavor with it. Coleman’s process insured a pungent and assertive powdered product.

The R.T. French Company introduced its bright, turmeric-colored mustard, “cream salad mustard,” at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. The company presented the mustard as a condiment for hot dogs.

Mustard is essential in food products such as mayonnaise, salad dressing, soups, and encased meats. Mustard is low in calories, high in protein, and cholesterol-free. It contains healthy amounts of minerals such as calcium, magnesium, potassium, and niacin. Used in crop rotations, mustard enhances yields of wheat and barley. A mustard crop can even break disease cycles in cereal grains. Mustard oil is essential in some food processing and it has potential non-food applications such as toxic gas, biodiesel, and industrial lubricants.

Mustard seed is generally available in three varieties.

Canadian Grain Commission

Sinapis hirta–white or yellow mustard, Brassica juncea–brown, oriental, or Indian mustard and, Brassica nigra–black mustard.

Yellow mustard seeds have the lowest oil content, making it the mildest of the three mustards. Indian mustard is also called Chinese mustard. Black or brown mustard seeds yield the hottest mustard.

Seed type, preparation, and additional ingredients all contribute to a mustard’s taste as well as its “heat.” Mustard’s signature sharp, pungent flavor results from mixing either ground seed or powdered mustard with a liquid. The mixing starts a chemical reaction that releases compounds responsible for mustard’s characteristic heat.

There is no generally accepted ’hotness scale’ for mustard. However, one might take note that the condiment was often spooned out with a light hand. Special tiny condiment spoons evolved for use with mustard.

This delightful French mustard spoon was part of the 2010 CITR ornament swap. It came from MissHomeEcsDaughter (Brenda).

A mustard’s strength also depends on the temperature of the liquids used. Hot liquids inhibit the chemical reaction. If everything else is the same, mixing hot water with mustard powder yields a mild mustard. Mixing cold water with mustard powder yields a hot mustard. By extension, if mustard is added to a dish early in cooking, much of its pungency is lost.

Other mustard facts include:

• Freshly-made, water-based mustard will lose its bite within several hours. However, the addition of an acid— such as vinegar—stops and sets the reaction.

• Mustard is among the most powerful antibacterial plants known today. Plus, the presence of vinegar and salt, greatly reduce the chance that prepared mustard will spoil. For that reason, mustard does not require refrigeration; it will not grow mold, mildew, or harmful bacteria.

• Unrefrigerated mustard most likely will lose its pungency more quickly than refrigerated mustard. If stored for a long time, unrefrigerated mustard can acquire a bitter taste.

• Basic mustards are made of

— mustard seeds and/or powder,

— liquid to start reaction (water, wine, bourbon etc.),

— an acid to set reaction (lemon juice, or vinegar—sherry, apple cider), and

— salt. Always salt to taste, but mustards generally use

about one to two teaspoons per cup of prepared

mustard.

• Bitterness is a byproduct of the mustard reaction and is present immediately. However, the bitterness fades after a day or so. Prepare your mustard a few days in advance of serving. Some sources suggest one or two weeks of aging.

I gathered this mustard information in order to audition a few specialty mustards for this holiday’s gift giving. The first audition:

Hot Peach-Mango Mustard: Printable

I’m a mustard fanatic and often drool over lists of exotic mustards, swooning over some of the fruit-mustard combinations. I’m partial to peach and mango, so I thought I would develop a hot peach-mango mustard. The original plain mustard recipe calls for 6 tablespoons of mustard seeds along with the mustard powder. I chose to use black and oriental mustard seeds. The combination produces two groups of chemical reactions and results in a wonderfully complex mustard.

3 tablespoons whole black mustard seeds

3 tablespoons whole oriental mustard seeds

1/2 cup mustard powder

1/2 cup white wine

3 tablespoons sherry vinegar

2 teaspoons salt

generous helping of patience

3/4 cup frozen peach slices

3/4 cup frozen mango cubes

juice 1/2 lime

Many of the recipes I found suggested grinding the whole mustard seeds for a few seconds in a spice or coffee grinder. I decided to use a mortar and pestle because I thought a greater number of uncrushed seeds would add a pleasing crunch to the mustard. It did.

Mix ground seeds, mustard powder, and salt in a non-reactive bowl. Stir to eliminate any lumps. A small whisk was very helpful here.

Pour in the wine. Stir well. Wait five or ten minutes, then add the vinegar. Stir well again.

I wanted to taste test the mustard before adding the fruit. As a result, I stopped here, covered the bowl with plastic wrap, and refrigerated the mustard for 24 hours. I can testify that freshly made mustard is extremely bitter. By the way, at this stage the mustard has the consistency of thin soup. After it ages for a day, the mustard will be thick and creamy. I promise!

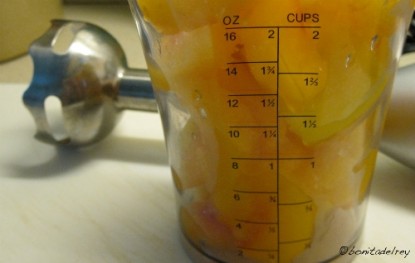

When you’re ready to continue, buzz the peaches and mango with a regular or immersion blender. You should get about 1 1/2 cups thick fruit puree. Add puree, along with lime juice, to mustard.

Pour or spoon into a glass jars. Wait at least 12 more hours before using. Mustard made this way will last several months in the fridge. This recipe made three 4 oz and one 8 oz jar.

Making mustard at home can be a bit like buying a cat in a sack—you can’t predict the outcome until you’ve completed the recipe. Here are a few remedial steps you can take to rescue a mustard that has run amok.

• If, after three or four days, you find the mustard is still too pungent for your taste, a few seconds in the microwave will mellow the mustard. An alternate mellowing method relies on a bit of lime juice. You’ll note that’s the course I took.

• If the fruit puree was on the thin side and your spreadable mustard is now more like a dipping sauce, consider adding a bit of almond flour to help thicken the mustard. Make almond flour by grinding almond slivers in a spice or coffee grinder.

When ordering mustard seed, be sure to look for the Latin names. There is some ambiguity in the use of brown, black, hot, Chinese, oriental, and Indian as descriptors.

S. hirta, White or yellow mustard seed is much larger than those of the other two species and measures 6 grams per 1,000 seeds.

I found the mustards, sold by weight, over the Internet. However, most recipes specify volume measurements. So, I guesstimated the volume of available packets: a 4 oz bag of regular mustard powder is about 1 cup dry measure. The yellow mustard seed and hot (or oriental) mustard seed yield about 1 cup dry measure for 3 ounces, while whole brown mustard seed seems to be about 3/4 cup for 4 ounces.

B. juncea, hot or oriental mustard, has the largest seed, 3 grams per 1,000 seeds while B. nigra black (or brown) mustard seed measures about 1.5 grams per 1,000 seeds.

The numbers:

Powdered mustard — $ 1.25

Hot seeds — .30

Brown seeds — .43

Peach/mango puree — $ 2.00

Total — $ 3.98

The recipe yielded about 20 ounces mustard at a cost of about $0.20 an ounce.

The audition was a success! Now there are more flavors in the wings: hot and spicy blackberry mustard made with blackberry beer and blackberries; apricot ginger mustard, raspberry honey mustard, rosemary orange mustard, and chocolate merlot(!) mustard.

No matter what your taste, try your hand at making a few fancy pants, exotic mustards at home. It’s fun, simple, inexpensive, and rewarding. Mustards are a healthful addition to any diet. They are great for forming a myriad of crusts and sauces for chicken, beef, pork. And, don’t forget, any mustard can easily be transformed into a pretzel dipping sauce for game day. Once you order your mustard seeds and powder, turn toward Saskatchewan, address our CITR sisters—Astrid and pdelaney—and ask “Please pass the mustard, eh?”

Editor’s Note: While it may seem strange to see two mustard posts in the same week, they were both done independently without the other knowing…and submitted on the same day. There must be something to this homemade mustard!

Do you have a recipe post or kitchen-related story to share on the Farm Bell blog?

See Farm Bell Blog Submissions for information, the latest blog contributor giveaway, and to submit a post.Want to subscribe to the Farm Bell blog? Go here.

lisabetholson says:

Bonita, this is great, I made mustard this last summer and everyone liked it. I will have to venture on with my mustard making. Thank you, great job

On November 2, 2011 at 9:56 am

bonita says:

Privileged: Hi, it seems like I may have not been clear about the cost of the Peach-Mango mustard. The numbers used to get to 20¢ an ounce, do not reflect the purchased cost of the mustards. I took the cost of each mustard, guessed how many recipe’s worth each package was, and then computed the cost per recipe. As it is, the powdered mustard was $2.59/4 oz, Hot Yellow seed and regular Yellow 1.74/3 oz each; and whole brown, 2.59/4 oz.

I ordered my spices from The Spice House. But, I didn’t purchase the spice based solely on price. I ordered from a place that also stocked Tamarind Paste and Vanilla Bean Paste.

Good luck trying the mustard, it is really easy and fun.

On November 3, 2011 at 8:27 pm

privileged says:

Bonita,

Thanks so much for the reply! I understand now what you meant. I’m so impressed at how much cheaper it is to make it at home. I’m new to this site and loving the blog posts more and more everyday, keep them coming! 😉

On November 5, 2011 at 8:58 am